Dosa Kitchen: Ancient Foods, Contemporary Convenience

Dosa: crispy, chewy, fresh off the griddle, nutritious, gluten free since the year 800 AD, vegan, fermented, digestible, and delicious. It’s the traditional, convenient, dinner-in-a-pinch South Indian street food that you can put in a waffle iron, serve for any meal, use as onion-ring batter, and it would probably make an astoundingly good fried Oreo, too. Perhaps a simple pancake slathered with peanut butter and honey, or covered with creamy chicken bechamel, or scattered with melted cheese and accompanied with a simple salad. It’s really hard to mess this up. Especially with Dosa Kitchen’s help.

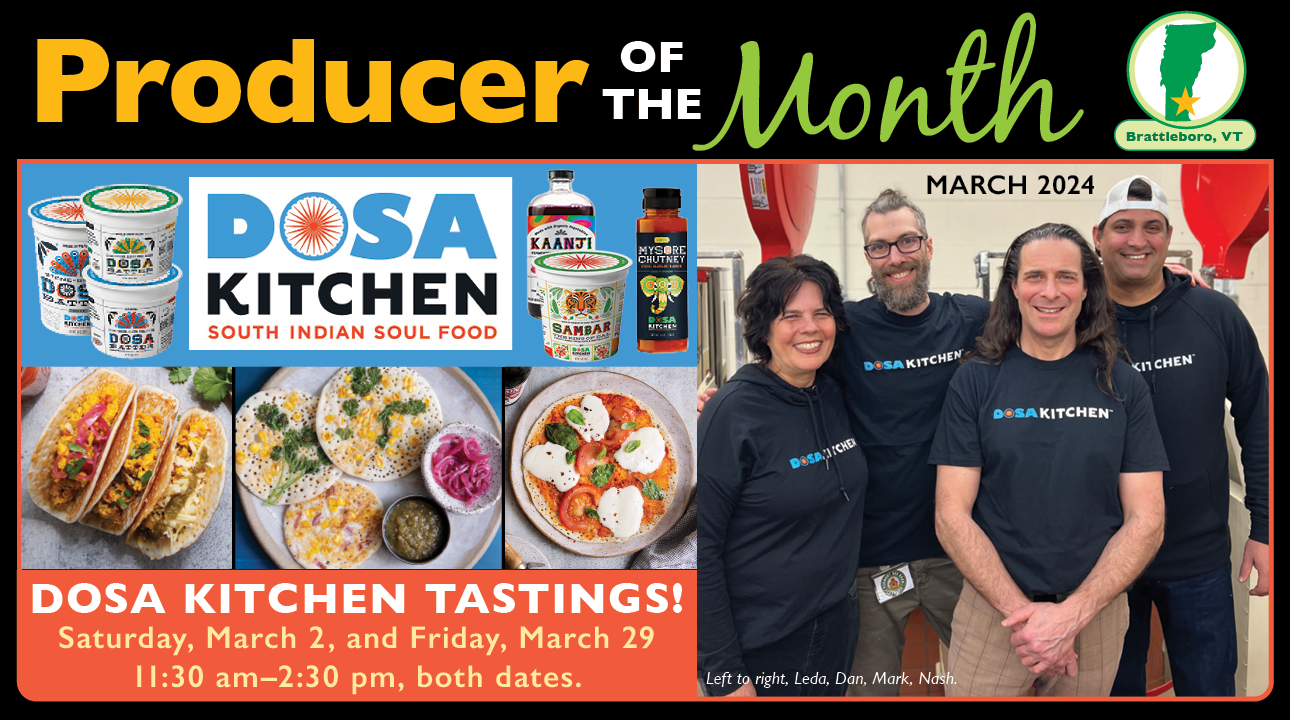

Did you know we have some of the best dosa batter, ready to turn into whatever crispy iteration of crepe or pancake you desire, right here at the Co-op, in the dairy case next to the local fresh tortillas? Is this not incredible?! Next to it you’ll find another traditional South Indian food: Mysore chutney, a wonderfully flavored, hot-sauce-like, classic accompaniment to dosa. Add to these another typical dosa companion: sambar, found in the frozen section, which is a sort of lentil soup that has more depth and complexity of flavor than any convenience food shopper has a right to expect. And lastly, head over to the fermented beverage cooler and you will find kaanji, a wild, refreshing beet and carrot tonic with a hint of mustard seed. I don’t know if we here in Brattleboro truly appreciate what we have here. Why we are not eating these things every weekend night, I do not know.

It was in 2009 that Leda Scheintaub and Nash Patel moved to Brattleboro, VT, from New York City. Leda is a Long Island native, and grew up in a family of healthy hippies on the cutting edge of alternative health and wellness modalities—her mom was a yoga teacher when it was still really weird. Nash is an Anglo-Indian/Parsi man who grew up in Hyderabad, the large capital city of Telangana, India. They started dating a few years after Nash moved to New York City and was working as a waiter in an Indian restaurant that Leda frequently went to.

Both Leda and Nash’s journeys towards Dosa Kitchen were winding. Leda remembers dreaming of opening a cafe and bakery as a child, but her path first took her to college, where she studied political science, and then to a master’s degree in Latin American studies. After her formal education, she wound up as a managing editor at Penguin Books, but her love of food and cooking drove her to seek out something different. She attended the Natural Gourmet Institute while still employed in publishing. The twin skill sets of food and publishing naturally led to work as a cookbook editor, author, and recipe tester.

Nash actually started his work life at a dosa restaurant in Hyderabad at age fifteen, but he was determined to go to technical school to learn about air conditioning systems. He did achieve that goal, but the job that got him out of the country was again in food service, at an American fast-food franchise in Oman. Nash met lots of people from the US there, and bonded over a shared love of country music (of which he and his brother had been fans all through their youth). It was partly that experience that inspired him to come to this country. Eventually, he landed in Queens, NY, where his brother and other family and friends already resided.

When Leda and Nash met, Leda had already spent some time in Brattleboro. She loved it here, so she’d rent an apartment in town for a couple months and work on recipe testing. Nash would join her for some of the time, and in 2009 they decided to permanently move here. They got married on a whim at the Common among a small group of friends.

At that point Leda still had what she calls her “New York brain,” which basically means she felt an urgent desire to Do It, whatever “it” was, NOW. Thus, just three days after their move they had already created a small business called Pepper Water, selling Indian foods at the Brattleboro Winter Farmers’ Market. (Pepper water is a common Anglo-Indian soup made with tomatoes, tamarind, and other ingredients.) In the meantime, Leda continued working on cookbooks. Nash helped her with recipe testing, and soon started working at Against the Grain, the gluten-free bread and pizza company.

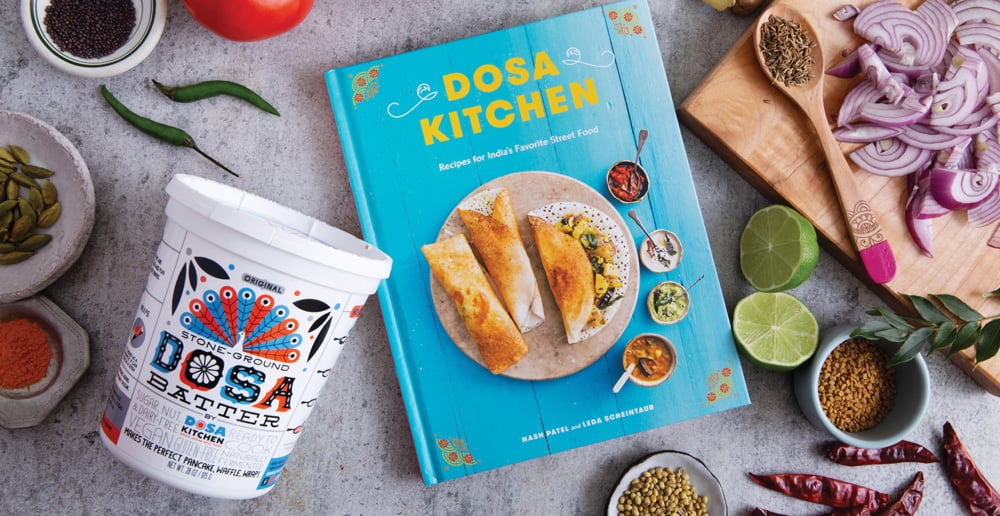

A few years later, Nash and Leda opened the Dosa Kitchen food truck, and it was an instant hit. They’d already started exploring the idea of selling pre-made dosa batter, but Leda, who is good at taking advantage of all the support she can find, was advised by her business mentors to hold off. Dosa is a super common food in South India, but here in the States there are only small pockets of awareness, and that was even more true in the 2010s, which made the barriers that much higher for customers to feel comfortable buying such a product for home preparation. The food truck was a perfect way to serve food, get to know the community more, and educate people about this wonderful South Indian staple. A few years later, a cookbook was published (Dosa Kitchen: Recipes for India’s Favorite Street Food, sold here at the BFC). They briefly had a restaurant space on Elliot Street in Brattleboro, but several factors led them to return to the truck, which can’t be beat for efficiency. Their truck is still open to the public in the warmer months right outside Dosa Kitchen’s new home, a roomy production facility at the Winston Prouty Center, where they produce and package two varieties of dosa batter (rice and millet), Mysore chutney, sambar, and kaanji.

Dosa Kitchen is growing. Leda and Nash recently hired two people, both friends from the Against the Grain days: Dan Rosen is their sales specialist, and Mark Mayer is a production associate. Both were hired within the last few months. Ultimately they hope to have Dosa Kitchen products available all along the eastern seaboard, and with the distributors they’re currently partnered with it seems likely they’ll be able to accomplish this within a few years. They’ve laid the groundwork for their business to thrive in many ways, including the visual parts of the business. When searching for someone to design labels for their budding retail wing, they admired the Upper Pass Brewery beer can labels as just the sort of bold, colorful design style they were looking for. Ultimately they decided to contact the artist who created them, Mike Mullan. Using Indian decorated trucks as inspiration, the result is a beautiful collection of intricate, fun, magical packages that match the quality of the foods found within.

The biggest pieces of equipment in the Winston Prouty space are the two giant dosa grinders that they bought about a year ago. They are cream-colored vats about the size of a dunk tank with bright, shiny red tops. There is a matching pair of smaller ones, too, from when their production needs were lighter. Inside these machines are multiple granite wheels that grind the soaked rice and lentils for the dosas—almost like a small, contained version of a grist mill. Nash told me that this version of the dosa wet grinder is an innovation of the last few years; when he worked at a dosa restaurant as a teen, the equipment was much less efficient and more labor intensive. To make the dosa batter, the lentils and rice (or millet) are soaked and ground separately, and combined after they’ve gone through the machines. The texture they’re looking for is like that of sugar. Once it’s all been combined with water, fenugreek seeds, and salt, the batter is left in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room for eight hours, after which it looks “like a volcano.” Note that the batter doesn’t have any added culture or anything to make it ferment—this is wild fermentation, which means it’s our good old Vermont microbes that are souring the batter. The same is true of the kaanji.

So, what exactly are dosas? They’re sort of like crepes, but they’re crisper and chewier. There are lots of variations across South India and beyond, but they all share a couple things in common: they are made of ground lentils and rice (or, less often, another grain); the batter is lightly fermented; and they are cooked in a thin layer on a griddle (also called a tawa). Sambar (lentil soup), various chutneys (they run the gamut of chili-based to coconut-based), idli podi a.k.a. gunpowder (a ground, dried lentil and spice mixture that can be mixed with oil on the plate), or Indian pickles are the typical accompaniments, depending on which region of India you’re in. Frequently they are eaten at breakfast, but, again, like a crepe, it’s also common to have one for lunch or dinner. But unlike a crepe, they don’t flop or sag; they can be folded, rolled, or flat—they will keep their chewy shape, regardless. Sometimes there are vegetables scattered in the batter as they cook, sometimes they’re filled with peas, cheese, or potatoes, and just as often they’re eaten plain. As you can see, they’re quite versatile!

Here in the West, some folks might be more comfortable starting with something more familiar to get into the dosa groove. Dosa Kitchen batter is perfect on a waffle iron, for instance. And you can use it to get a nice, crunchy coating on any food worth frying. It’s also wonderfully allergen-free: this millenia-old recipe just so happens to fall perfectly in line with current health trends (wheat free, gluten free, lactose free, sugar free, vegan, and fermented)!

Dosa Kitchen’s kaanji is also an ancient yet of-the-moment product. It’s a traditional Punjabi beverage, but theirs is the first bottled version available in the US. Beets are the base for this tart, salty, zingy, probiotic beverage, just like for kvass, which is traditionally from Eastern Europe—Leda’s ancestral land. The similarities between kvass and kaanji link Leda and Nash’s heritages through food and, as with sourdough bread, kombucha, sauerkraut, and all wild fermented foods, it maintains the core qualities of its original recipe while being the product of microscopic lifeforms native to vastly different parts of the globe. Leda and Nash are also developing a recipe for a carrot kaanji.

All of Dosa Kitchen’s products use traditional, authentic Indian culinary techniques and ingredients, but they’re also super accessible and easy to enjoy, sort of like really high-caliber home cooking. The sambar, for instance, is made with what is known as a tarka: spices and aromatics are “tempered” in oil on the stovetop, and then added to the lentils and vegetables along with a bit of tamarind. Like the Mysore chutney, it’s the same recipe that is used for their food truck menu, and has passed the test of many a South Indian family that has approached the Dosa Kitchen truck with much suspicion! Many times, a large family will hover in the distance while one family member approaches to order a single serving of dosa and sambar as a test of their quality. Once sampled, they invariably come back to order full meals for all. Over and over again Leda and Nash have won over doubting Indian visitors, who say the dosas are the best they’ve had, and the kaanji is just like home.

Dosas are immune to any restrictive ideas of purity: this is ancient food that is alive in more ways than one, in that it is both fermented and ever-evolving. To make waffles and pancakes out of dosa batter, to add a few frozen veggies to a heated pot of sambar on the side, or use some Mysore chutney on a taco: none of this is against the rules. This is food that invites experimentation and innovation, and that is ready to be embraced by our little town and our wider region.

Click here for a link to a dosa recipe!

By Ruth Garbus

Visit the Dosa Kitchen website to sign up for their newsletters and get lots of great recipes

About Producer of The Month

Shop Online

On Sale Now!